EVENT: A BRIEF HISTORY OF TECHNOLOGY & ART IN CHINA, CHAPTER ONE: COMPUTER-BASED ART (DECEMBER 26 2025–JANUARY 26 2026, CHONGQING, CHINA)

A Brief History of Technology & Art in China, Chapter One: Computer-Based Art

December 26 2025–26 January 2026

Chongqing Contemporary Art Museum

No. 108 Huangjueping Zhengjie, Jiulongpo District, Chongqing, China.

Hours 9:00–17:00, last entry 16:30, closed Mondays (free admission)

Chongqing Contemporary Art Museum is currently hosting A Brief History of Technology & Art in China, Chapter One: Computer-Based Art, an exhibition that treats computation as medium rather than tool. Visitors handle controllers, enter VR environments, and test interactive works, an orientation that feels particularly acute in relation to game-based art, where meaning tends to surface in input, latency, and the tactile grammar of feedback rather than in detached contemplation.

Presented as the first instalment in a longer historiographic project, Chapter One proposes a timeline that begins with 1990s personal-computing experiments – produced on systems that now function as archaeological strata – and extends to contemporary installations built with real-time 3D engines. The show includes works produced with platforms and software associated with that first domestic wave of computing (MS-DOS, early Apple systems, and even office applications such as PowerPoint), placing “obsolete” interfaces in dialogue with contemporary interactive media.

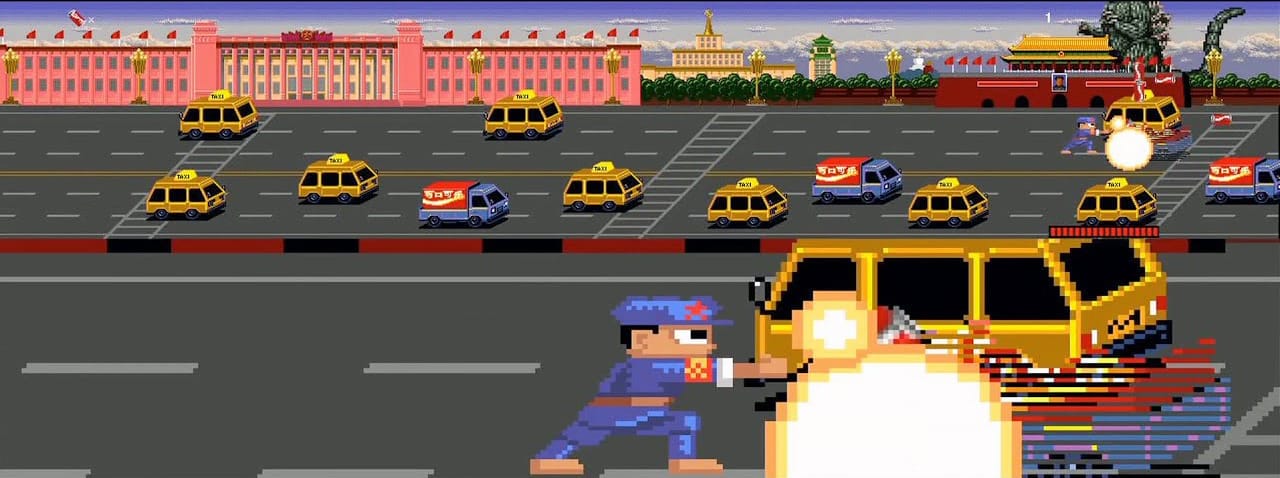

A focal point for many visitors is Feng Mengbo’s Long March: Restart (2008), a large-scale interactive videogame installation that reworks the visual grammar of side-scrolling action titles into a politically charged, historically referential format.

The work carries an unusually dense institutional record: acquired by MoMA in 2009, exhibited at PS1 in 2010, featuring dual large-scale projections (approximately 80 by 20 feet) that dwarf the viewer-player. The PS1 presentation emphasized the installation’s spatial ambition and its departure from conventional gaming interfaces). The work was subsequently presented at ZKM in Karlsruhe, Germany, as part of their game art programming, positioning it within the institution’s sustained critical engagement with interactive media and playable art since the 1990s. It was also contextualized through UCCA’s Restart exhibition (2009), which traced the piece back to Feng's earlier Game Over: Long March paintings. This genealogy matters because it shows the translation of painterly syntax into interactive systems, a shift in material logic rather than mere remediation. Finally, LACMA acquired the work in 2014, with curator Christina Yu Yu describing it as “one of the most iconic artworks created by a Chinese artist in the past 30 years”, reinforcing its canonical status beyond new media/Game Art circles and into broader contemporary Chinese art discourse

In Chongqing, the work operates as more than a canonical game art touchstone. It anchors the exhibition’s larger claim that China’s computer-based art history cannot be narrated only through screens as display surfaces. Input devices – controllers, interfaces, embodied actions – are positioned as archival objects in their own right, materially constitutive rather than merely instrumental.

Beyond Feng, the exhibition proposes a deliberately mixed ecology: works associated with net art and speculative interface practices appear alongside game-derived and engine-driven projects. Cao Fei’s The Birth of RMB City: Engine Film (2009) reinforces this, treating real-time 3D production as a cultural form with embedded politics: spatial, labor-based, speculative. Art21 provides a critical commentary in the video below:

The featured artworks also includes Wu Ziyang's Agarta (2024), a puzzle videogame, and Marc Lee’s Speculative Evolution (2024), which demonstrates the curatorial frame extends beyond retrospective preservation to test how contemporary interactive art circulates across game logics, software art, and networked display.

Another prominent component is the VR section titled “Virtual Art Museum,” presented in partnership with Shenzhen’s Pingshan Art Museum, featuring a multi-user environment in which visitors can manipulate virtual sculptures and encounter other participants in real time, less solitary VR demo, more shared gallery space where embodied interaction generates social presence.

The exhibition also foregrounds collaborations between Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, highlighting projects that combine coding with electronics and mechanical design. This institutional infrastructure matters precisely because it refuses the art meets tech cliché. The exhibition argues, implicitly but insistently, that computer-based art in China is a history of labs, curricula, and interdisciplinary production conditions, not a succession of solitary auteurs.

updated (Jan 12 2025): here are some photographs taken by our friends Rizosfera