GAME ART: RUTHERFORD CHANG’S GAME BOY TETRIS (2013–2018)

Rutherford Chang: Hundreds and Thousands

17 January–12 April 2026

UCCA Center for Contemporary Art

798, No. 4 Jiuxianqiao Lu, Beijing, China

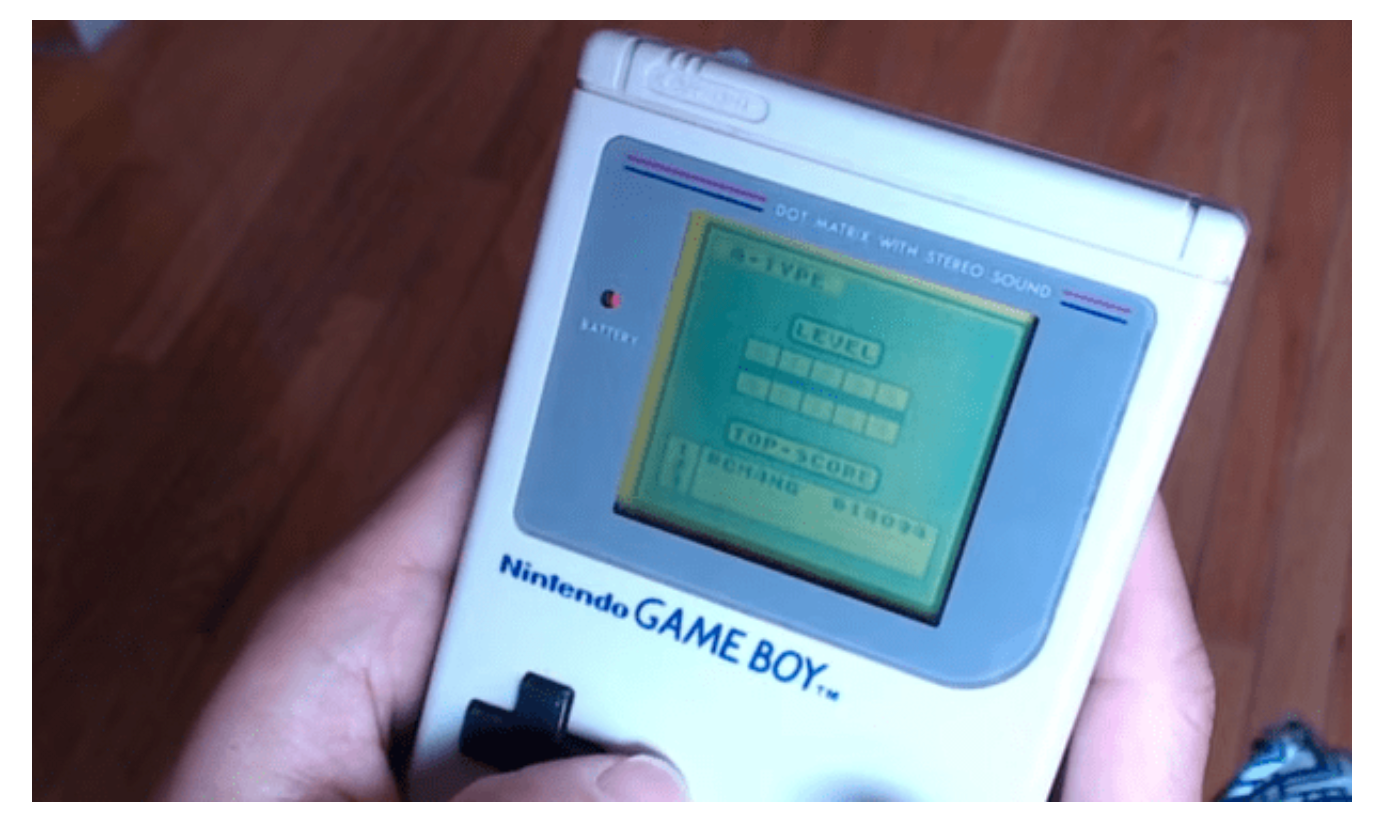

Between 2013 and 2018, conceptual artist Rutherford Chang (1979-2025) recorded himself playing Tetris on an original Nintendo Game Boy, uploaded each session to gameboytetris.com, and presented the growing archive alongside the console(s) used to generate it. In the new UCCA Center for Contemporary Art’s survey Rutherford Chang: Hundreds and Thousands (17 January–12 April 2026), Game Boy Tetris appears as “2,139 digital videos,” exhibited with letters addressed to Nintendo Power magazine and the handheld hardware itself.

The gesture is simple (play, record, upload) yet the work’s public legibility depends on a tighter conceptual hinge: a self-imposed metric of improvement structured by competitive record-keeping. UCCA’s exhibition text frames the project as “a deliberately quixotic attempt to approach the world record,” noting that Chang “briefly ranked second” on Twin Galaxies in 2016, with a top score listed as 614,904 (also described as the tenth highest recorded at the time of writing). That aspiration is inseparable from repetition and fatigue, but it is also inseparable from the institutional grammar of records: submission, verification, and the public conversion of many hours into one ranked number.

Chang’s thousands of recordings are not merely documentation; they are the evidentiary substrate that record culture demands. Twin Galaxies, recognized by Guinness World Records as an early videogame adjudication service, originated with an arcade opened in Ottumwa, Iowa (1981) and, historically positioned itself through rules, contests, champions, and the routine collection of high scores from dispersed sites. In Carly A. Kocurek’s account of “world record culture,” Twin Galaxies is significant because it helped normalise competitive play as a public narrative and, equally, because it stabilised “records” as a knowable category through protocols and gatekeeping.

Read through this lens, Game Boy Tetris does not sit “outside” the epistemology of competitive gaming; it operates inside that epistemology while importing durational, conceptual-art logics into it. The labour becomes intelligible as record pursuit only because a third-party infrastructure exists to certify the pursuit. The archive is thus less an autonomous artwork than a negotiated object, produced by Chang, validated through external standards, and circulated as rank. (Rhizome’s 2016 editorial on Chang’s Real Live Online performance, written by Micheal Connor, describes 1,747 documented plays and reports a best effort of 614,094 points, “second place worldwide,” citing Twin Galaxies).

Chang’s letters to Nintendo Power are not an eccentric add-on; they are a second channel of address that intensifies the work’s archaeology of gaming authority. Rhizome reproduces a 2015 letter and notes that it was not published because the magazine had folded three years earlier. The gesture is therefore structurally “address without reception”: an appeal to an institution that no longer functions, performed anyway, and then exhibited.

Scholarship on Nintendo Power is helpful here because the magazine historically helped manufacture a particular kind of player, training readers into Nintendo’s preferred literacies while brokering the boundary between corporate voice and fan community, as Amanda Cote notes. Chang’s letters, written after closure, read like a petition to a withdrawn embassy: a deliberate anachronism that marks the collapse of print-era certification (mail-in recognition, editorial mediation) and the rise of platform-era proof (leaderboards, streams, searchable archives).

Additionally, the Game Boy is not neutral equipment. Its portability, constrained display, and durability encode a particular intimacy of play: hands, screen, battery life, repetition across places. That material grammar matters for a work organised around endurance and incrementalism. It also matters historically: by 2013 the device reads as retro hardware, a mass-produced consumer artefact carried forward into a new media ecology. In game studies terms, the handheld’s bodily scale and branded materiality are part of how gaming is lived, remembered, and made collectible as this conversation attests.

Chang’s performance oscillates between Twitch’s attention economy and Rhizome’s curatorial framing. Connor reports that his gameplay was presented “for one hour each day at noon” on Rhizome.org during Real Live Online, an event co-presented with the New Museum. That constraint is curatorially sharp: it converts Twitch’s default temporality (always-on, endlessly scrollable) into scheduled broadcast, an imposed rhythm closer to television than to platform drift.

At the same time, Twitch’s monetisation infrastructures made of subscriptions, donations, ads, sponsorship, and other revenue pathways are built to reward engagement and ongoing affective labour. Chang’s streaming persona, by design, withholds the usual “channel value” tactics. The stream becomes a kind of anti-spectacle that still remains fully legible as labour, precisely because Twitch makes labour visible as a metricised relationship between time, attention, and value.

Across Chang’s broader oeuvre, Game Boy Tetris reads consistently with an artist preoccupied by exhausted cultural forms and mass production, objects whose value has been naturalised, emptied out, or overdetermined. UCCA situates the project alongside We Buy White Albums and CENTS, linking Chang’s practice to collecting, repetition, and cultural memory over two decades. ArtAsiaPacific’s obituary likewise stresses his “eccentric collection of mass-produced cultural artifacts,” including thousands of White Album pressings, and positions his work as a sustained inquiry into value, wear, and circulation.

Under that rubric, Game Boy Tetris is not “gaming as content.” It is a durational method for extracting meaning from an ordinary system by exhausting it, then exhibiting what remains: time recorded, proof accumulated, authority addressed, rank pursued.