GAME ART: CAMILLO RESTREPO’S SPACE INVADERS (2024)

Camilo Restrepo’s Space invaders 1 (2024) and Space invaders 1418 (2024) lift the visual grammar of Taito’s 1978 arcade shooter and plug it into the long, unfinished story of Colombia’s narco-wars and their ecological afterlives.

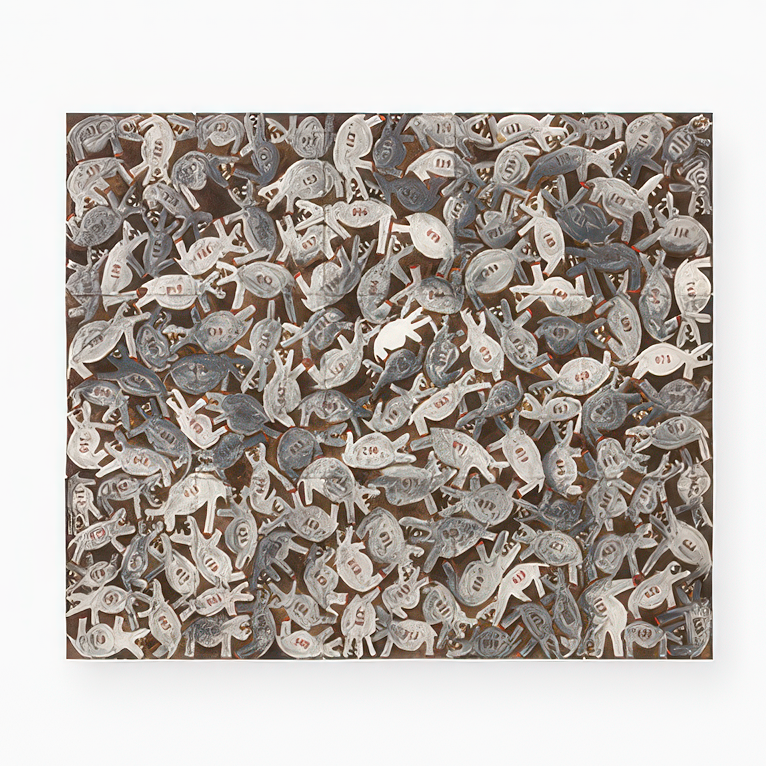

Both large vertical works were presented in the solo exhibition Cocaine Hippos Sweat Blood at Galería La Cometa, Madrid, in 2024. In that show Restrepo revisits the now infamous “narco-hippos,” the hippopotamuses imported by Pablo Escobar to Hacienda Nápoles in the 1980s, whose feral descendants still roam Colombian rivers and wetlands, a living monument to the failures of prohibition and the entanglement of drug money, spectacle and environmental damage.

Restrepo was born in Medellín in 1973 and grew up during the escalation of drug trafficking and narcoterrorism. He has often described witnessing car bombs, corpses in the street and the everyday intimidation of cartel violence while coming of age.

His drawings and paintings reprocess that history through a deliberately cartoonish, “low” visual vocabulary: bright colours, comic grotesques, fragments of advertising and pop culture. Critics have stressed how his large-scale works “represent the drug violence that for decades has besieged his native Colombia,” using cut, scraped and taped paper that carries literal scars. Restrepo experienced first-hand “the rise of drug trafficking and the emergence of narcoterrorism,” growing up amid mafias that reshaped every layer of Colombian society, fuelling violence and inequality. His practice is described as a construction of “multiple blocks of meaning and unstable entities” that combine into dense compositions. The central thread is “the global battle between truth and fiction,” which in Colombia appears where violence meets popular culture. The work exposes the connections between drug trafficking, national elites and their manipulation of reality, offering a satirical critique of the failed war on drugs and providing counter-narratives where institutions and civil society have fallen short.

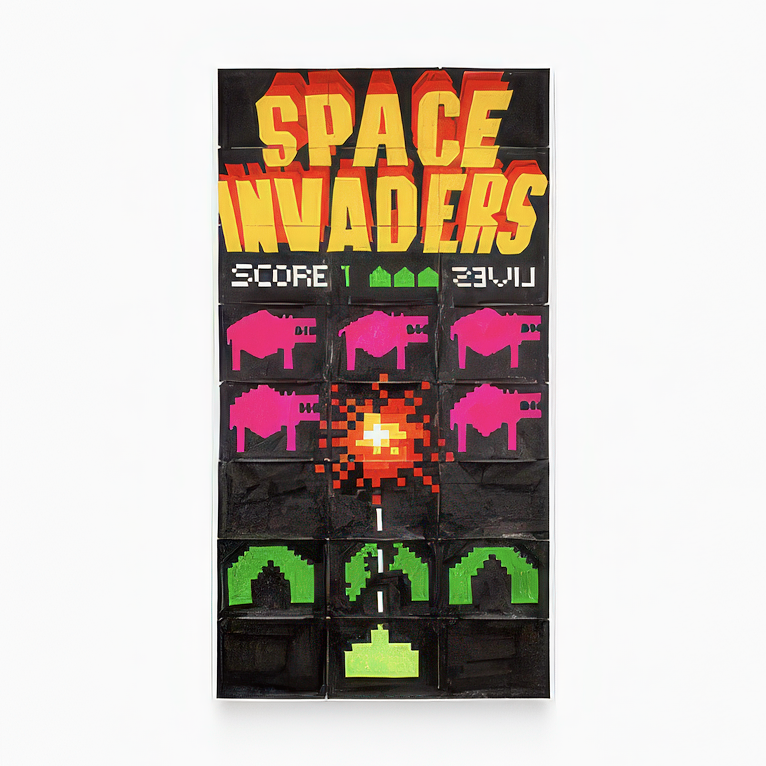

In Space invaders 1 the familiar black screen of the arcade cabinet becomes a stacked grid of dark rectangles. At the top, Restrepo copies the game’s logo in screaming yellow and red. Below it, the monochrome “SCORE 1” counter appears next to three small green lives icons, and to the right a shorthand for the high score, figures that already signal the logic of accumulation, quantification and competition that defined early acrades.

The aliens, however, are gone. In their place stand hot-pink, pixelated hippos, arranged in three columns. They hover above a line of lime-green bunkers and a simplified player cannon at the bottom centre. A vertical sequence of white “bullet” pixels links the cannon to a central explosion rendered as a jagged cluster of red, orange and yellow squares.

Restrepo holds onto the graphic minimalism of Space Invaders but rewrites its cast. The “invaders” are no longer anonymous sprites from outer space but stylised versions of Escobar’s hippopotamuses, recoded as enemies in a fixed shooting gallery. Within the larger Cocaine Hippos cycle, those animals already function as allegorical figures, remnants of narco excess and symptoms of an ecological crisis produced by the drug economy. Here they are flattened into targets. The piece frames the hippos as a swarm to be eliminated, turning culling policies and media panic into a game scenario in which violence becomes a matter of hand–eye coordination and scorekeeping.

At the same time, the tactility of Restrepo’s materials resists the clean, frictionless surface of the screen. The brushstrokes in the black background, the slightly misaligned grids, the seams of tape, visible in reproduction as well, disturb any nostalgic reading. Instead of celebrating the arcade as a harmless retro icon, Space invaders 1 suggests how easily its visual language can be retooled to narrate state violence, militarised conservation and the quantification of life.

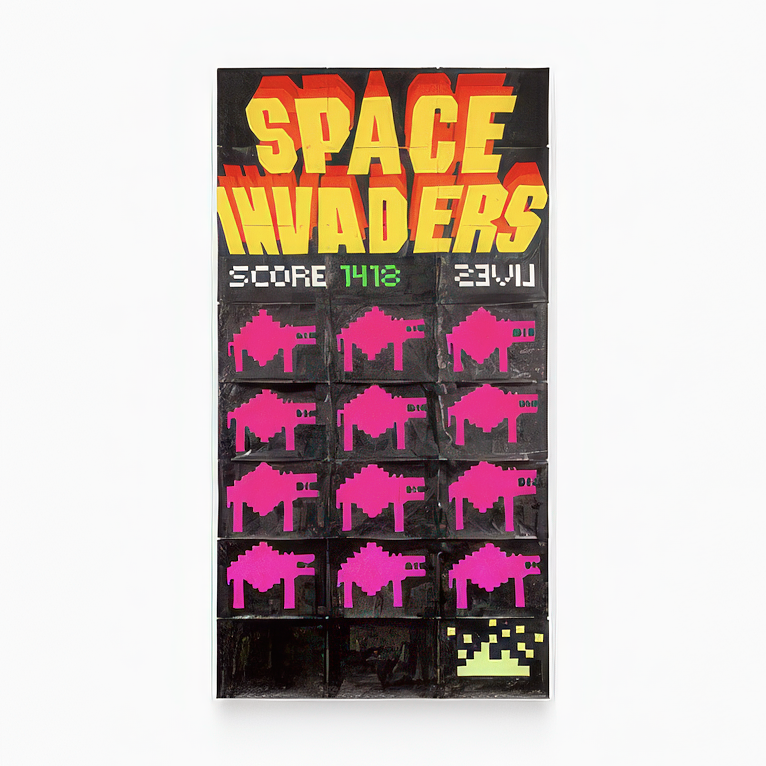

If the first canvas presents a recognisable game moment – player firing, shields still in place – Space invaders 1418 shows the aftermath. The logo remains. The score has jumped from a miserable “1” to an oddly specific “1418”. The hippo invaders now occupy every available slot in a denser grid, advancing inexorably downward. The green bunkers have disappeared. In their place, at the bottom right, a pale, glitchy fragment stands for the player’s cannon, as if already hit and flickering out of existence.

The composition reverses the power relation implied by the arcade original. Instead of a heroic player defending earth from alien hordes, Restrepo’s field of hippos feels unstoppable. Their uniform magenta bodies read as statistics more than individuals: numbers of animals, victims, hectares, dollars. The artificial precision of “1418” on the scoreboard strengthens that impression. Even without a direct documentary reference, the work encourages viewers to read the score as a tally of casualties or infractions, rather than points in an abstract game.

Within Cocaine Hippos Sweat Blood, this is consistent with Restrepo’s broader strategy. Works such as Fosa común and Escena del crimen invoke forensic language and imagery, confronting viewers with mass graves and police evidence markers while maintaining the same acidic palette and cartoon sharpness.

The Space invaders paintings transpose that logic to a digital interface: the battlefield becomes a pixel grid and history is reframed as a series of (deranged) “levels.”