EVENT: MONUMENT VALLEY: THE TRILOGY (DECEMBER 19–JANUARY 4 2025, SHEFFIELD, UNITED KINGDOM)

National Videogame Museum

Castle House, Angel Street, Sheffield, S3 8LN, United Kingdom

19 December 2025 – 4 January 2026

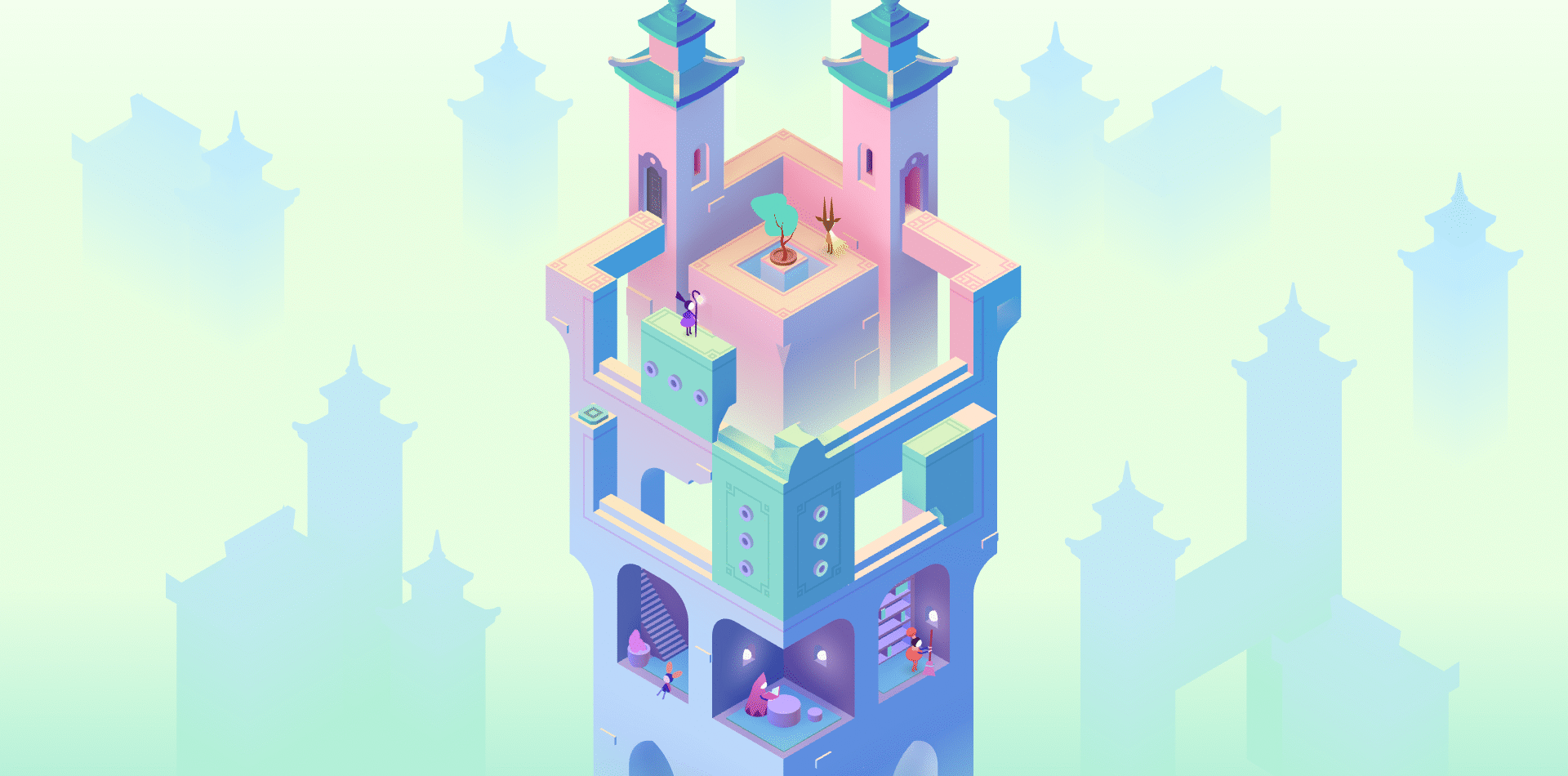

This December, the National Videogame Museum (NVM) turns its galleries into a walkable thought experiment, hosting Monument Valley: The Trilogy, a showcase devoted to ustwo games’ celebrated puzzle series and its signature “impossible” constructions. Running 19 December 2025 to 4 January 2026, the exhibition pairs hands-on play with production materials, inviting visitors to see how a mobile-scale design language becomes a museum encounter.

At its centre is a 3D model of a maze level, presented alongside Building the Impossible: The Making of Monument Valley 3, a behind-the-scenes video focused on the newest instalment’s development and translation into exhibition form. Around that anchor, visitors can play the full trilogy and join themed activities, like designing geometric puzzles and characters, or spending time in a reading nook stocked with illusion-focused books and puzzle material.

The original Monument Valley launched in 2014 and quickly became a reference point for mobile games that treat composition, colour, and pacing as core mechanics rather than surface polish. A sequel followed in 2017, shifting the emotional register while retaining the series’ compact, diorama-like levels.

Monument Valley 3 first arrived on Netflix Games on 10 December 2024, then expanded to wider platforms, its PC and console release landing in July 2025. A free post-game expansion, The Garden of Life, released 3 December 2025.

The institutional framing here matters because the series has long circulated as something you complete in quiet, on a phone, on a train, in the lull between messages. In the museum, that intimacy gets re-tuned: the trilogy becomes not just a set of puzzles, but a case study in how contemporary game design borrows from graphic art, architectural draughtsmanship, and perceptual psychology.

Calling Monument Valley “Escherian” is more than a convenient shorthand. M. C. Escher’s best-known architectural images operate by exploiting a viewer’s habits: we assume consistent depth cues, stable gravity, and coherent edges. The drawing offers enough local logic to persuade the eye, even as the global structure refuses to add up.

Vision science has a crisp term for this family of effects: impossible objects figures that can be represented in 2D but cannot exist as consistent 3D forms. The classic account is the Penroses’ 1958 paper, which formalises the paradox and helps explain why these images “work” perceptually despite their physical impossibility.

Monument Valley translates that principle into interaction. Its levels behave like architectural proofs you manipulate until a path becomes true. Rotation, sliding bridges, and shifting platforms do not merely reveal a hidden route; they change what counts as adjacency. A staircase becomes connective tissue not because the world suddenly obeys physics, but because the game grants priority to a particular viewpoint. In that sense, the player is not solving within a stable space: they are authorising which spatial reading governs movement. This is why the “impossible” in Monument Valley feels strangely calm. The series does not ask you to wrestle the paradox into submission. It asks you to accept that perspective is part of the system’s rule-set, then proceed.

Museum presentation makes this logic easier to grasp. A phone screen can hide the labour of design behind effortless gestures; a large-scale display and a physical model push you to notice the construction: the way a level is built from clean planes, crisp silhouettes, and selective depth cues, with ambiguity carefully distributed so the illusion can flip when you intervene. That’s also where the NVM’s curatorial choice lands well. By foregrounding a model and a making-of feature, the exhibition shifts attention from “pretty puzzles” to process: tools, iteration, and the craft of turning an image-based paradox into a navigable route.

The show is also a snapshot of how museums are recalibrating their relationship to game culture. NVM positions itself as the UK’s dedicated institution for videogame heritage, and it explicitly frames this showcase as part of a wider commitment to preservation, interpretation, and public access. On the studio side, ustwo games has presented its work as mission-driven as well as design-led, publicly emphasising its B Corp status and social commitments alongside its catalogue.

Monument Valley is a strong match for that institutional conversation because it has a long-standing reputation for bridging audiences. You can approach it as an elegant puzzle box, or as a primer on how images govern action. Either way, the museum context makes the point plain: the trilogy is not simply about impossible architecture. It is about how contemporary media trains perception: gently, persistently, and with a designer’s hand on the vanishing point.