EVENT: AI AND THE PARADOX OF AGENCY (MARCH 13 2026–JANUARY 17 2027, UMEÅ, SWEDEN)

AI and the Paradox of Agency

March 13, 2026–January 17, 2027

Opening: March 13, 5pm–12am, with talks and presentations, tours, workshop, DJ and bar

Bildmuseet at Umeå University

Östra Strandgatan 30B Umeå, 903 33 Sweden

From March 13, 2026 to January 17, 2027, Bildmuseet in Umeå, Sweden turns artificial intelligence into a curatorial problem. AI and the paradox of agency brings together twenty-five years of work by nineteen artists and collectives to ask a simple, uncomfortable question: when algorithmic systems enter daily life, who actually decides what happens: users, engineers, corporations, or the software itself?

The exhibition stands out because that question is posed through games, simulations, and game-adjacent interfaces as much as through more familiar installation formats. Bildmuseet explicitly flags “interactive games and immersive installations” alongside sculpture and a drone-read textile, and several of the invited artists have built their practices around game engines, real-time worlds, and playable AI scenarios. Curated by Sarah Cook and Katarina Pierre, with support from WASP–HS and the Wallenberg foundations, the show reads like a survey of how game-driven art has become a primary way to think about AI, not just a stylistic option.

One of the key figures here is Lawrence Lek, whose work has long treated game engines as instruments for speculative fiction. In his practice film, videogames, and electronic music converge into a connected “cinematic universe” of simulated cities and sentient infrastructures. Recent projects such as NOX Pavilion invite visitors into a corporate training environment in which they play trainee therapists counseling malfunctioning self-driving cars: AI clients in need of guidance. The player’s controller input becomes a kind of clinical protocol, while non-human agents speak back through dialogue trees and behavioural scripts. (We visited Lek’s solo show in Los Angeles in October).

In this light, Lek’s presence in AI and the paradox of agency signals a focus on how simulated environments redistribute initiative between human and machine actors. His smart cities, populated by surveillance architectures and sentient vehicles, are built in the same software that drives commercial games, yet they are tuned to foreground feedback loops of obedience, care, and resistance. The “paradox” in the exhibition title resonates strongly here: the more the player appears to steer the session, the more the scenario reveals prior decisions embedded in code, corporate policy, and infrastructural fantasy.

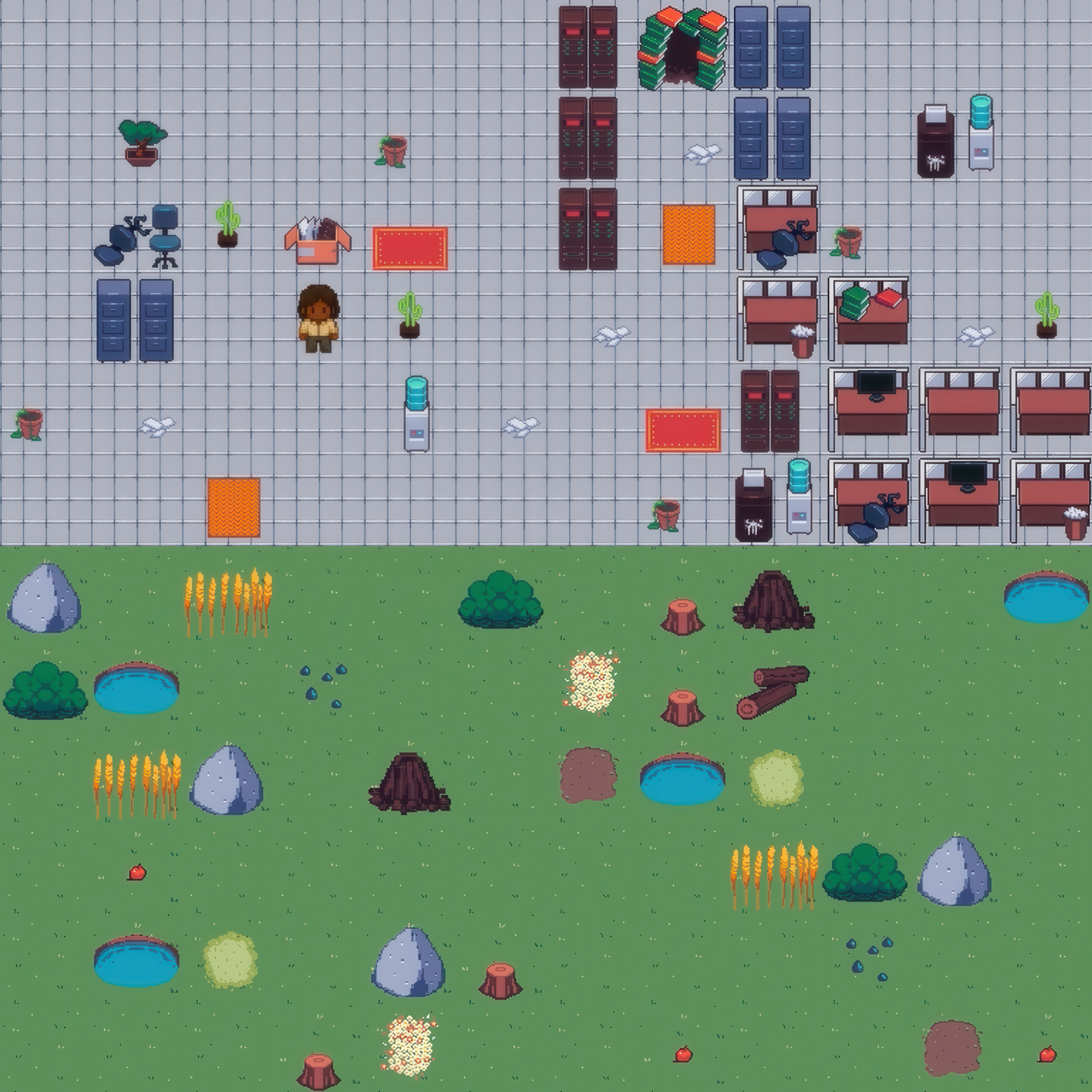

The inclusion of boredomresearch (Vicky Isley and Paul Smith) pushes the game connection in a different direction. Since the late 1990s they have explored artificial-life systems through computational art, often using techniques borrowed from videogame development. Works such as Ornamental Bug Garden 001 combine game-style rendering with artificial-life modelling to create closed ecosystems of algorithmic creatures whose behaviour evolves in real time.

Here, “gameplay” is less about clear objectives than about observing swarms and ecologies under conditions defined by the artists’ code. The viewer occupies a position familiar from strategy games and god-sims – hovering above a landscape, watching populations fluctuate – yet the emphasis rests on fragility and environmental stress rather than on optimisation. In the context of an AI exhibition, these artificial-life gardens read as allegories of training environments and simulation laboratories: sandboxes where rules, parameters, and reward structures quietly determine which behaviours flourish and which are suppressed.

Yuri Pattison’s work further tightens the link between AI, infrastructure, and game technologies. Recent projects such as dream sequence (working title for a work in progress) are described as “generative and mutable game engine motion picture/play,” with imagery and sound modulated by local atmospheric data. The piece runs on a game engine but behaves more like a weather-sensitive film that never repeats in the same form.

Rather than supplying players with explicit choices, Pattison’s simulations expose how sensor data, networks, and industrial systems quietly script experience. That sensibility fits neatly within a show dedicated to agency: decision-making is outsourced to a mix of environmental measurements and algorithmic routines, while visitors occupy a kind of delayed spectator position, watching an AI-driven scene drift according to inputs they cannot directly see.

Florian Model, another artist in the exhibition, approaches similar questions from the angle of social and behavioural modelling. His artistic research into “Purposeless Abundance” imagines autonomous agents roaming resource-rich, goal-free simulations, some exploring, some imitating, some getting stuck in loops. Here the game space is stripped of explicit missions; what remains is a playground for emergent routines, imitation, and boredom. The result looks like a game in which objectives have evaporated, leaving bare the push-and-pull between programmed incentives and improvisation.

Other participants extend game logics into questions of memory, extraction, and geography. Planetary Portals, a research collective including Casper Laing Ebbensgaard, Kerry Holden, Michael Salu, and Kathryn Yusoff, has been developing projects that examine the colonial afterlife of gold and diamond mining through AI analysis of archival photographs and critical cartographies. Their work treats datasets and maps as contested terrains, closer to strategy game interfaces than to neutral records: sites where extraction is planned, simulated, and potentially resisted.

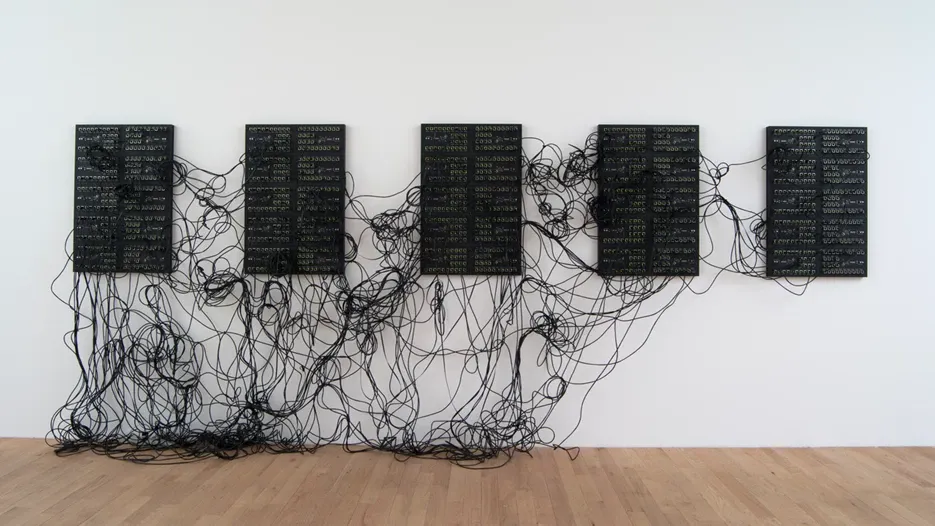

In the Bildmuseet show, this orientation sits alongside contributions by artists such as Addie Wagenknecht, Nicolas Gourault, Caroline Sinders & Romy Gad el Rab, and Paola Torres Núñez del Prado, who each in different ways probe the politics of training sets, pattern recognition, and acoustic interfaces. Even when a literal game engine is absent, the logic of AI as rule-based system, with uneven access to the rules, remains central.

Curators Cook and Pierre frame AI and the paradox of agency as a response to the uneven adoption of AI systems, where the greatest benefits and most significant risks cluster around those who own and maintain the infrastructure rather than those exposed to it.Instead of illustrating this with predictive policing dashboards or stock-image generators, they foreground artists who have long treated interactive systems, simulations, and game worlds as testing grounds for social and technical arrangements. An accompanying book, edited by Cook and including interviews with participating artists, is planned for the exhibition period, promising further detail on how these practices conceive of AI as collaborator, subject, or adversary rather than mere tool.

In a moment saturated with shiny image generators and techno-solutionist rhetoric, AI and the paradox of agency suggests that some of the sharpest questions about artificial intelligence are being raised in spaces that look suspiciously like videogames, and that the controller in the visitor’s hands may already be sharing its grip with the systems running underneath.